Will Prevagen’s Deceptive Advertising Ever End?

Eight years after TINA.org alerted regulators, supplement ads continue to convey deceptive and misleading memory improvement claims.

Counting up issues with study sure to be a sleep aid.

| | Bonnie Patten

UPDATE 10/3/19: On Wednesday, the district attorney of Alameda County, California, filed a complaint against MyPillow for alleged violations of a 2016 settlement that prohibits the Minnesota-based company from misleading consumers about the effectiveness of its pillow. The complaint centers on a sleep study that MyPillow started promoting late last year in connection with claims that the pillow reduces the symptoms of sleep apnea sufferers, among other things. It cites a number of problems with the sleep study, including that the study is neither placebo-controlled nor double-blind, despite claims by MyPillow that it was both. The complaint comes six months after TINA.org alerted the district attorney’s office to the company’s violations of the 2016 agreement. Our original post follows.

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (RTC) study is regarded as one of the most valued research methodologies around for examining the effectiveness of a product or intervention. And it’s also a great marketing tool. Companies love to tout their product as “clinically tested” or “clinically proven” in order to encourage consumers to part with their hard-earned dollars.

Unfortunately, TINA.org has seen a worrisome trend of companies playing fast and loose with what they claim to be clinical studies in order to promote marketing messages that simply aren’t accurate. The list includes L’Oréal and its clinically proven fountain of youth for skin; Capillus laser hats, clinically proven to regrow hair; Sensa, whose sprinkles guaranteed weight loss with a doctor’s studies as clinical proof; Pom Wonderful juice, clinically proven to treat, prevent or reduce the risk of heart disease, prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction; and, more recently, Prevagen, clinically proven to improve memory. The problem with all these assertions, however, is that the research simply does not support the marketing message.

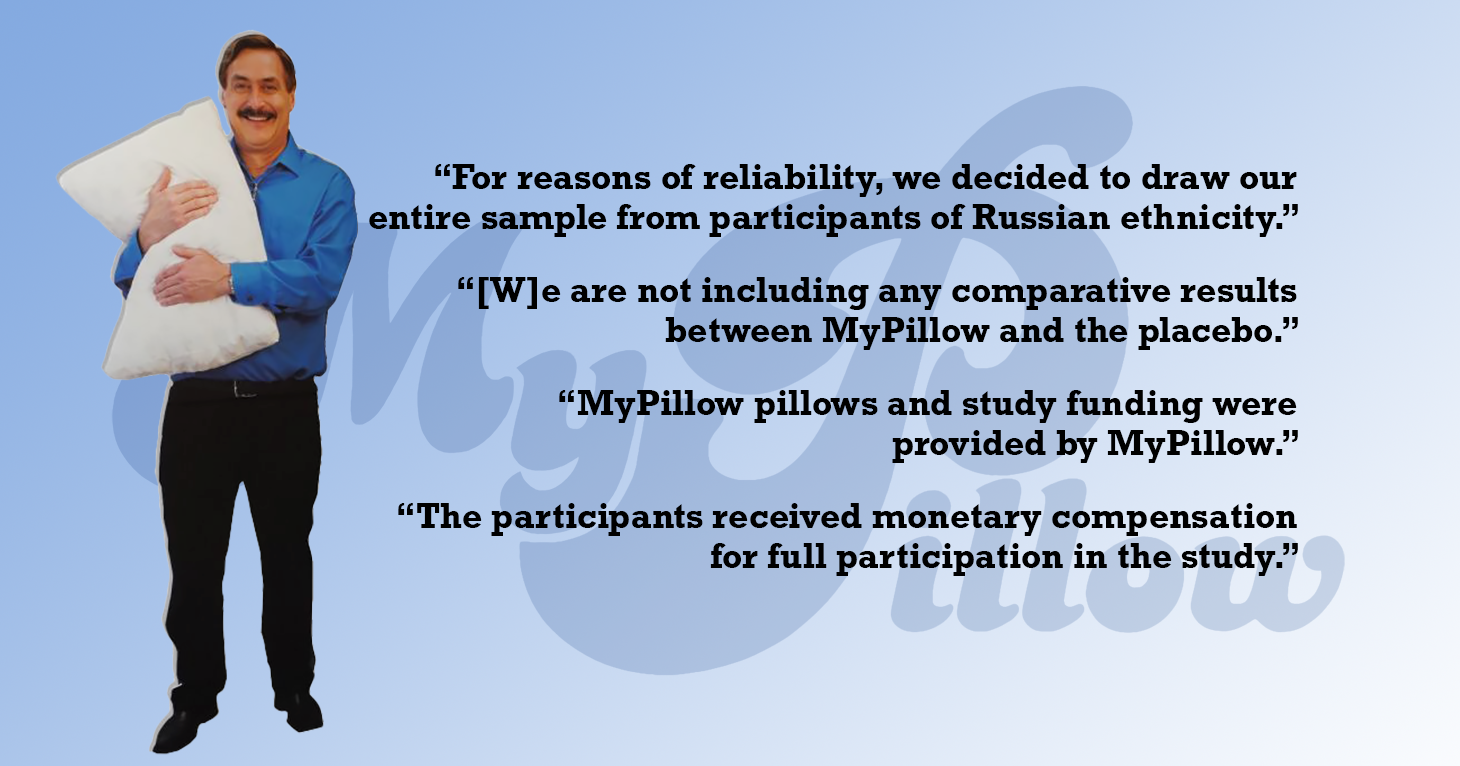

Joining the bandwagon is MyPillow, which recently published a sleep study on its website that claims to be a “double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of consumer-marketed MyPillow.” The problem is that the trial, which MyPillow paid for, appears to have been an unmitigated disaster that ultimately failed to yield competent and reliable scientific results. Here are a few of the problems the researchers had:

As a result, the researchers did not include “any comparative results between MyPillow and the  placebo,” which means the results of the study are neither randomized nor placebo-controlled. (In case you’re wondering, the placebo was not a foam pillow similar to MyPillow but a goose down pillow, though the exact size, fill amount, and brand is not disclosed in the published study. The researchers did indicate that they used a MyPillow Classic pillow supplied by the company, which leads one to wonder whether these pillows were imprinted with the standard MyPillow logo all over the casing.)

placebo,” which means the results of the study are neither randomized nor placebo-controlled. (In case you’re wondering, the placebo was not a foam pillow similar to MyPillow but a goose down pillow, though the exact size, fill amount, and brand is not disclosed in the published study. The researchers did indicate that they used a MyPillow Classic pillow supplied by the company, which leads one to wonder whether these pillows were imprinted with the standard MyPillow logo all over the casing.)

And there are other issues with the study:

I could go on but I think you get the gist of what I’m saying, which is that just because an advertiser says something is clinically proven doesn’t actually mean the advertising claim has been clinically-proven.

Eight years after TINA.org alerted regulators, supplement ads continue to convey deceptive and misleading memory improvement claims.

Of all the companies exploiting the pandemic, doTerra stands out as a steadfast recidivist.

And if you don’t know, now you know.