The Cost of Doing Business

Comparing the amount companies agree to pay to settle deceptive marketing charges with their annual revenue.

Know the answers to these questions to be sure that MLM isn't a pyramid scheme.

Forget about the celebrity endorsements, the uber smart scientist, the terrific product, and that kick-ass rags-to-riches speech you just heard. Because if a An inherently deceptive form of multi-level marketing where participants are told they’ll get paid for recruiting other participants, and not necessarily for selling products or services. Typically, participants must pay some sort of initial investment in order to join, and will then earn a commission for each participant they recruit. Unfortunately for the unsuspecting consumers, pyramid schemes are doomed to collapse because the number of potential participants is limited. is pitching to you, odds are most of what you’re hearing isn’t all that accurate or relevant anyway.

When you are trying to figure out whether a company really is a legitimate multi-level marketing organization (“Multilevel Marketing – a way of distributing products or services in which the distributors earn income from their own retail sales and from retail sales made by their direct and indirect recruits.”) or an illegal pyramid scheme, you need only do one thing: follow the money.

To ensure that you are not about to enter the tainted netherworld of a pyramid scheme, which could land you in legal hot water, make sure that you have answers to these seven money-related questions before you make any sort of investment.

1. Do you have to pay for the right to sell the product or service? For example, do you have to pay an entry fee, membership fee, bookkeeping charge, or headhunting fee (to name just a few)?

If the answer is YES, that’s bad. The company has just met one part of the legal definition of a pyramid scheme, and you need to be on guard. If the answer is NO, that doesn’t mean the company isn’t a pyramid scheme. It just means you need to answer more questions. If the answer is I DON’T KNOW, that’s bad too. Pyramid companies are masters of disguise, and one of their favorite ways to hide the true nature of their business is to bury the true details of the business. (More on this below.)

2. According to the company’s compensation plan, how are you going to make money?

The terms and conditions of an organization’s compensation plan can tell you a lot about what type of company you’re dealing with. So if you’re serious about joining the “team,” you must read the plan.

When reading the plan, consider these issues:

Is the company’s compensation plan clear and easy to understand, or, as one court put it, a labyrinth of obfuscation? If the compensation plan is a lengthy, confusing document with more bonus layers and conditions than hearty lasagna, that’s not good. Pyramid companies are masters of making their plans so difficult to understand that no one can figure them out. The complexities of the compensation system help to obscure the true nature of the business. Thus, if you can’t understand the plan, run (don’t walk) away from it.

When reading the compensation plan (assuming it’s readable), determine how much money you are required to spend every month (or year) to make money. (Note: Odds are the plan won’t tell you about all the possible charges you might incur, such as shipping and handling charges, but it’s a good place to start.) Pyramid schemes typically require you to pay them money either by charging you for the right to sell the product or service (see point 1 above), or conditioning your compensation on continual mandatory purchases of the product. This later charge is known as “Inventory loading is the practice of requiring participants to purchase merchandise in order to receive commissions..”

If the company is pushing inventory loading, odds are the compensation plan will require hefty purchases in order for you to qualify to earn maximum commissions (or perhaps that fancy car). You should avoid getting involved with a company whose compensation plans are based on mandatory purchases.

Does the plan compensate you for recruiting others into the organization? One of the hallmarks of a pyramid scheme is its “recruitment focus” — which is when a company bases most of your compensation on getting more people to join the team rather than the retail sale of the product or service to the general public. But in order to avoid the perception that they are paying for recruitment, savvy pyramid schemes mess with the concept of who the “general public” is and what a “retail sale” is.

Their primary line of defense, as always, is smoke and mirrors: make the plan so confusing that no one can tell who’s getting paid what for what. But here’s the thing, no matter what the plan says (or the CEO for that matter), sales to your recruits, your own self-consumption of the product or service, or sales to other individuals working for the company do not count as retail sales to the general public.

If the MLM’s compensation plan is not tied to selling stuff to a bunch of strangers wholly unrelated to the company, that’s a huge warning sign that you’re dealing with a pyramid scheme. (See point 4 for further exploration of this muddled point.) One further note on this point, many MLM compensation plans have some CYA provisions that their lawyers add in order to defend against pyramid allegations. The three most common CYA provisions (also known as the Amway rules) are as follows:

Sorry to disappoint but this is not the end of your inquiry. Even if the company’s written policies appear to be on the straight and narrow (as in, it has the three CYA provisions), whether the company actually follows its own rules and how it does is what truly matters. While the companies’ rules may be carefully crafted to appear like a legal MLM, in practice it may still be operating an illegal pyramid scheme, which brings us to our next point.

3. How does the business actually function in practice?

The existence on paper of the three CYA rules is only a partial step in the pyramid scheme inquiry. More important is finding out whether there is evidence that the company actually enforces the rules and that the rules actually serve to deter inventory loading and encourage true retail sales.

When it comes to actually instituting effective methods for verifying sales to the public or accepting unsold merchandise, pyramid schemes fall short. If the company simply requires that you “promise” to be good and follow the rules, or that you simply sign a piece of paper that says you were good and followed the rules, that’s not much of an enforcement mechanism to deter inventory loading and should be viewed warily. Unless the company is regularly auditing its sales force to ensure that its distributors won’t be contestants for the next episode of inventory hoarders, you should stay away.

Similarly, while the plan may say it will take back unused inventory, pyramid schemes have a variety of ways to deter distributors from attempting to return unsold goods. One of the common tricks of the pyramid trade is to demand that you compensate the company for commissions or bonuses the company gave you for the sales you were supposed to have made from the inventory you are trying to return. This punishment can be quite a deterrent to trying to send back product.

4. Will you make more money recruiting new people or selling the company’s product or service to strangers?

Be on your guard when you are getting the answer to this question because your idea of what “the public” means and the MLM’s nattily dressed, white-teethed pitchman’s definition of “the public” may be quite different. Another way to ask this question may be, “excluding the business’s own internal sales force, and a distributor’s own personal consumption, how much of the product (or service) is sold to the general public?”

If it’s an illegal pyramid scheme, odds are the answer will be “I don’t know,” or “the company doesn’t track that” if the company even answers at all. If the company is operating a pyramid scheme, retail sales are not forthcoming because the compensation system is designed to reward recruitment much more than retail sales. Meaning, the company doesn’t really care about retail sales so it doesn’t track them, and if it did track true retail sales figures, the number would be so low that it would simply be used as evidence that the company is a pyramid scheme.

You see a pyramid scheme cannot save itself simply by pointing to the fact that it makes some retail sales. In order to stay on the legal side of the equation, an MLM’s economic profit center must be on retail sales to the public.

5. Can you actually make money selling the product or service to the public?

Calculator required. What is the suggested retail price (SRP) of the product or service you’re being asked to sell, and is that SRP competitive compared to similar products in stores or on the web? If the product is not truly unique you may have difficulty selling it at the SRP. Check websites like eBay for the company’s products – too many sellers could mean excess inventory, low prices and little to no profit for you.

Further, pyramid companies are masters of nickel and diming you. Make sure you know how much you are going to have to pay for things like shipping and handling, which can be outrageously expensive, in order to obtain your inventory. Also, look into what the sales tax and income tax will be, what your business expenses will be (such as gas and mileage and event planning), and if there are restrictions on how or where you can sell the product or service.

Inquire what kind of training and mentorship will be provided in teaching you how to sell the product or service. If a company isn’t forthcoming with information or help in how to truly sell the product on a retail level, that is a bad sign. All too often with pyramid schemes the only guidance that is given is from the person who joined the company two hours before you did.

Finally, are there any monetary incentives for you to engage in retail sales? (And again, when we say “retail sales,” we mean are there any monetary incentives to sell the product or service to a bunch of strangers not involved with the company?)

6. How many people that join the company actually recoup their initial investment? (Or put another way, what is the failure rate of participants?)

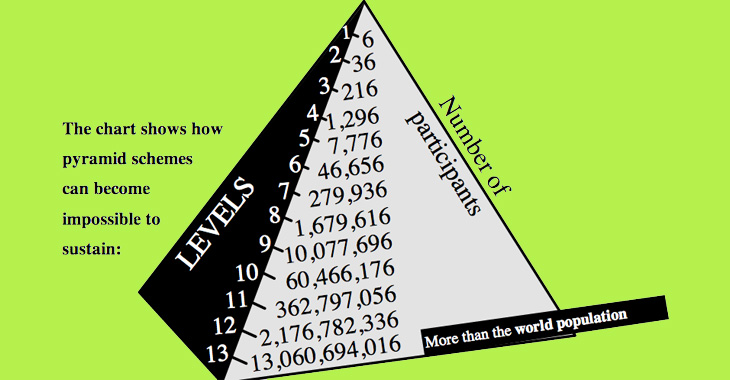

Conservatively speaking, at least 85% of the people that join a pyramid scheme will fail. This, my friends, is a guaranteed fact. And no, it’s not because most people just don’t understand the system, or aren’t smart enough, or true believers, or just didn’t invest enough money, time and effort.

The vast majority will fail because that is the way pyramid schemes are structured to work. The vast majority absolutely must fail in order for the company to compensate the small number of people at the top. Don’t believe it? Ask the company to show you its distributors’ average earnings. If you observe that the vast majority of people are making less on an annualized basis than they would at McDonald’s that’s a definite sign you may have uncovered a pyramid scheme.

7. How will you make millions?

If people are making money primarily from recruitment, then you will not make millions. Those rags-to-riches stories that you’re hearing about – well the only way they’ve made real money is by feeding off of the likes of you. Less than 3% of those that join a pyramid scheme will make any meaningful money and the odds clearly indicate that it will not be you.

If any of the answers to the above questions give you cause for concern, then stay away from the company. It’s likely a losing proposition.

Comparing the amount companies agree to pay to settle deceptive marketing charges with their annual revenue.

From fairwashing to fragrance, consumers have plenty to watch out for in 2021.

A network marketing coach doesn’t deliver on his (expensive) promises.