Ad or Not? Snapchat and DJ Khaled

Is DJ Khaled the key endorser on Snapchat?

What makes an ad . . . well, an ad?

On television, the distinction is generally clear: Commercials are recognizable immediately as such and, thanks to DVR, easy enough to skip. But on the web and even in traditional print newspapers, it’s becoming increasingly harder to spot the difference between real content and paid advertisements. Pop-up and banner ads are easily identified as ads — but what about that article in your Sunday newspaper or that post you’re reading on Reddit? Did someone pay to have it placed there? Thanks to Advertorials, or paid sponsored content, that may or may not be properly labeled as such., it’s not always so easy to tell.

And that’s the idea.

So called “native advertisements” are ads intended to blend in with a website, magazine, or newspaper’s normal content. Though labeled as paid content, native advertising doesn’t look like ads – which is why marketers are so keen on them. Native advertising is allowing marketers to find new ways to keep the attention of consumers who prefer to skip over ads. But this type of advertisement can border on deception.

For example, here’s a native ad from Facebook:

The “Suggested Post” disclosure in the top left marks the post as an advertisement, but it looks a lot like a Facebook update from a friend and blends right into Facebook’s newsfeed. Facebook sometimes even uses pictures and the names of your friends in sponsored posts, making your social network part of a native ad — a practice that upset many users and led to a class-action lawsuit. Facebook denied wrongdoing but agreed to a $20 million settlement. If the settlement is approved by a judge Friday, Facebook users will be able to opt-out of having their name and image being used in ads.

Several online and print publications have also experimented with similar “sponsored content,” another name for native ads. Twitter mixes native ads into users’ feeds.

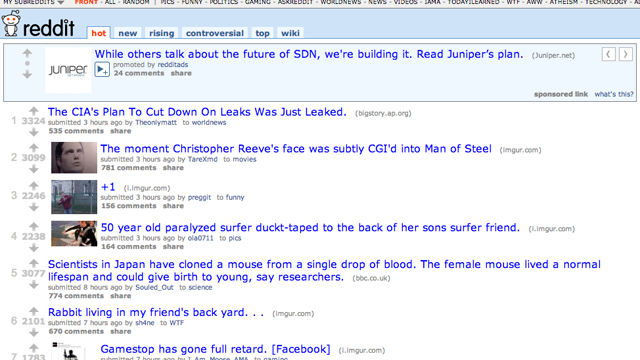

Reddit uses native ads at the top of its page.

Popular slideshow generator Buzzfeed routinely has a number of sponsored and partner posts on its homepage.

The Atlantic ran into trouble when it ran a native advertisement sponsored by The Church of Scientology that was poorly marked as an advertisement and confused a number of readers. And the Washington Post is trying out sponsored comments on its opinion page, allowing companies to pay to respond to editorials. This is an alarming development that creates the possibility of a publication writing an unflattering piece about a company so that the company will want to pay money for a chance to defend itself in a “sponsored comment” – something the company would have done in the past by writing a letter to the editor.

These new ads are effective at keeping a readers’ attention, but they blur the lines between ads and content. And if a reader can’t easily and immediate tell whether a native advertisement is indeed an advertisement, then the ad has at best confused the reader, and at worst deceived him or her. A deceptive ad by any other name is still a deceptive ad.

Is DJ Khaled the key endorser on Snapchat?

Olympians stumble out of the gate when it comes to disclosing sponsorships.

Just why exactly does People ‘love’ these products?