Best Reader Tips of 2021

This year reader tips led to dozens of ad alerts, as well as a complaint to regulators.

TINA.org files a complaint with federal regulators over shoemaker's deceptive made in the USA claims.

For more than a decade, New Balance has defied the law when it comes to marketing its athletic shoes as “made in the USA,” brazenly ignoring the legal definition for the term in favor of its own, less stringent standard.

Whereas the FTC requires that products marketed as “made in America” or “made in the USA” be “all or virtually all” made in the United States, New Balance says it labels and markets its shoes “made in the USA” when the “domestic value,” a term that it does not define, is as little as 70 percent.

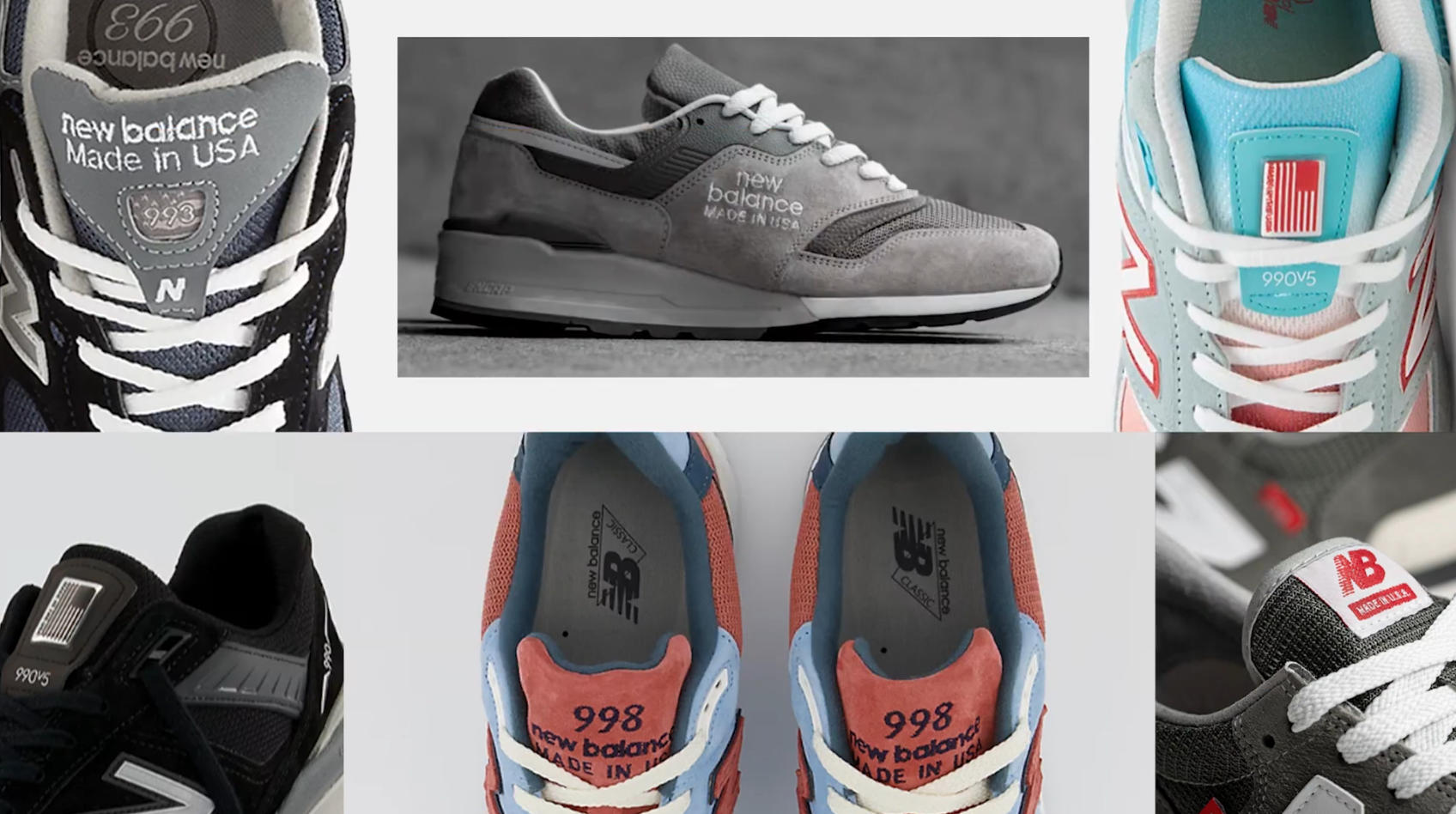

The Boston-based, multibillion-dollar company’s deceptive made in the USA labels appear on everything from the shoes themselves, sewn into the sides and tongues of the footwear, to the tags that are attached to the shoes, to the boxes and tissue paper that the shoes are packaged in. Several shoes even have “Made in US” in their name.

Yet consumers, many of whom not only prefer American-made products over imported products but are willing to pay more for them, may not know that New Balance’s criteria for labeling and marketing shoes “made in the USA” is different than the FTC’s.

Twenty-five years ago, New Balance escaped an FTC inquiry into its deceptive U.S.-origin claims without incurring any financial penalty. Now, armed with a new Made in USA Labeling Rule that gives it the authority to fine companies engaged in deceptive made in the USA labeling, the FTC can send a strong message that there’s a price to pay for misleading consumers.

On Monday TINA.org filed a complaint with the FTC urging the agency to open an investigation into New Balance’s deceptive made in the USA claims and take appropriate enforcement action.

As TINA.org noted in its complaint letter, the Made in USA Labeling Rule, which is the product of a TINA.org petition for rulemaking in 2019, prohibits New Balance from labeling:

any product as Made in the United States unless the final assembly or processing of the product occurs in the United States, all significant processing that goes into the product occurs in the United States, and all or virtually all ingredients or components of the product are sourced in the United States.

The rule applies to both physical and digital labels, such as those found on New Balance’s website and in social media posts by New Balance and its influencers, which include Olympic runner Emma Coburn.

Each violation of the rule carries a $43,792 fine. It only takes 23 shoes bearing a made in the USA label in violation of the rule to get to $1 million. New Balance says it makes or assembles more than 4 million pairs of athletic shoes per year in the United States. If each of those pairs is accompanied by at least one made in the USA label that violates the rule, New Balance could be facing more than $175 billion in fines for a single year.

The heart and “sole” of America?

New Balance doesn’t disclose on its packaging – or on any of its labeling or other marketing – the imported parts and/or foreign labor that make up as much as 30 percent of any one of its “made in the USA” shoes.

Fine print on the bottom and side of some shoeboxes only reveals that the shoe inside belongs to “a premium collection that contains a domestic value of 70% or greater.” (Meanwhile, prominent text on the side of the lid states, “made in the u.s. for over 75 years.”) Likewise, on the New Balance website, where none of the physical disclosures that accompany the shoes exist, a written disclosure on product pages that online shoppers must scroll down, past an “Add to cart” button, to see, states in part, “New Balance MADE contains a domestic value of 70% or more.”

However, during an appearance on Fox Business in 2011, then-president and CEO of New Balance, Robert DeMartini, divulged the secret sauce. Asked if all of the components of the company’s “made in the USA” shoes, “down to the laces,” are made in the United States, DeMartini responded (at around the 3:30 mark):

First of all, soles today, the bottom of the shoe, are not made domestically. The process that’s there is made overseas. We import the soles.

More recently, in a 2017 court filing, New Balance acknowledged that “certain materials used in some domestically manufactured shoes are imported from outside of the United States, including from some countries in Asia.” In 2013, the Wall Street Journal identified one of those Asian countries as China, reporting that New Balance purchases soles from two Chinese companies.

But the bottom line is the sole is a significant part of the shoe and therefore if it is not of U.S.-origin, the shoe cannot legally be marketed as wholly made in the USA.

To the extent New Balance employs a large number of American workers at its five facilities in Maine and Massachusetts who assemble shoes from imported parts like the sole, New Balance is well within its legal right to highlight that fact. However, as the FTC has made clear in dozens of closing letters over the years, marketers who overstate the degree to which products are “made in the USA” are violating the law.

How New Balance became emboldened following FTC inquiry

A consent decree is supposed to act as a deterrent against unlawful behavior in the future. But the one that came out of the FTC’s complaint against New Balance in the mid-1990s seems to have had the opposite effect on the shoemaker. Which is to say, it has only served to further embolden the company to violate the law.

This is perhaps not surprising due to the fact that the consent decree required the bare minimum of New Balance: that the company agree not to make “made in the USA” claims for shoes made entirely abroad. The FTC dropped what one lone dissenting commissioner called “the most important allegation” in the case, involving “made in the USA” claims for shoes assembled in the U.S. from foreign and domestic components.

No more than a year later, in 1997, New Balance was making its case against the “all or virtually all” standard, advocating instead for a 50 percent U.S. content standard that would benefit U.S. manufacturers that support American jobs. And it was making its case directly to the FTC, which had sought comments on proposed guidelines for the use of U.S.-origin claims. In its comment to the FTC, New Balance acknowledged the economic incentive for labeling products made in the USA. (Ultimately, the FTC decided to stick with its “all or virtually all” standard.)

All the while the company was increasing advertising spending, betting that the FTC either wouldn’t notice or wouldn’t take action. With revenues now eclipsing $4 billion, that gamble has paid off. And it will continue to pay off until the FTC steps in and makes New Balance follow the same rules every other made in the USA marketer is obliged to play by.

Find more of our coverage on New Balance’s deceptive made in the USA labels here.

This year reader tips led to dozens of ad alerts, as well as a complaint to regulators.

New Balance labels some of its shoes as “Made in USA.” Here’s why that’s a problem.

MADISON, CONN. September 20, 2021 – According to the latest investigation by consumer advocacy organization truthinadvertising.org (TINA.org), New Balance is deceptively marketing some of its athletic shoes as “made in…